The Daily Chronicle

Chapter 5 from The London Daily Press by H. W. Massingham.

A shrewd politician, who has had an important place in more than one party combination, said to me the other day, ‘The most influential paper in this country is the Daily Chronicle’ That was a very striking tribute to a journal whose history as a great London daily is shorter than that of any of its rivals, but I do not think it went beyond the truth. The Chronicle is in the happy position of a paper which is not hired to any party in the State. It has a strenuous and persistent voice in all the political and social controversies, and in particular a hold on some sections of the community incomparably stronger than that possessed by any of its contemporaries. But it is an independent paper. At the same time the main body of its teaching is probably nearer the inner mind of the left wing of the Radical party than anything which finds expression in the Daily News, the Pall Mall Gazette, or the Star. Just as its labour news is the most extensive and the most carefully edited that any paper presents to its readers, so its utterances on the whole social problem interpret the reasoned idealism, to use an apparently contradictory phrase, which marks the new spirit in politics, the renewed attempt to solve the problems that Chartism, the co-operative movement, trade-unionism, and what, for want of a better term, may be called Social Radicalism, in itself an amalgam of all these forces, have in turn attacked. The result is, that the Chronicle enjoys the confidence of trade-unionism and of the London working-men more conspicuously, perhaps, than any paper since Feargus O’Connor’s Star and the earlier and more advanced days of its modern namesake. Its editor has therefore been able to strike in in great social problems, like those involved in the County Council election, with an effect almost unexampled in journalism. By the general consent of both parties, the influence of the Daily Chronicle was the chief factor in the victory of the Progressive party; and the paper, whose early secession to Unionism was a source of bitter and outspoken regret to Mr. Gladstone, has had the main credit of preparing the way for a new political departure.

In the previous chapters I have mainly dealt with the established, and, perhaps it would be proper to add, the sedentary forces in English journalism. The Daily Chronicle is the active newcomer, the paper of progress, whose London circulation at least can be measured by that of the Daily Telegraph, while it is far superior to that of the Daily News. It touches more surely, more seriously, the great main arteries of English middle and working-class life, the doings of the churches and missions, the development of social movements, the personal record of labour leaders, than the Times, the Standard, the Daily News, or the Telegraph. It is the first English journal to give a regular and reasoned account of Greater Britain, the younger and stronger England beyond the seas, and it has been the first paper to grasp the meaning of the ‘nationalisation of letters’ the fact that the best books are to-day within the reach of all but the very poorest of our population. Its daily issue consists of a ten-page paper, one-tenth of which is regularly devoted to the world of books and the almost greater world of periodical publications. The value of this serious concentration on the best things in life has been conspicuous. The Chronicle depends less for its large and growing circulation on the baser sides of English life scabrous divorce cases, vulgar scandal, and the great betting madness than any of its contemporaries; it has largely dethroned the criminal from his place as the hero-in-chief of the English newspaper; and it has set up instead the social reformer, the practical worker, and the pioneer to fields of fresh intellectual and moral interests. The rigid rule laid down by its founder, Mr. Edward Lloyd, one of the most notable of modern captains of industry, that not more than half the paper should ever be devoted to advertisements, daily assures its readers of a thoroughly varied newspaper, perhaps unequalled for the variety and the careful selection of its intelligence. Above all, it has the surpassing merit of looking most closely to the city-nation, which, curiously enough, is the last concern of nearly all the leading London journals. ‘London first’ is the persistent motto of the Chronicle. It has reaped its reward in a renaissance of municipal spirit, which should in time make London a model instead of a byword to the leading centres of provincial life.

The Daily Chronicle is a very interesting example of a paper which has sprung, not as it were full-grown from Fleet Street, that great parent of modern journalism, but from small and unheroic beginnings as a local London paper. Even to this day the copyright of the famous old Clerkenwell News is preserved by the daily issue of a few numbers of the publication. The Clerkenwell News, however, was not started by Mr. Lloyd, and it never attained to any note except as a mere advertising organ. As such, however, first as a weekly, then as a bi-weekly issue, it had a large sale among the humbler classes, and in course of time assumed the title of the London Times, and attempted a daily issue. The Times, however, successfully resisted this poaching on historic preserves, and the earlier attempts to establish it as a rival of the great organs already in the field were not successful. The real history of the Chronicle began when Mr. Edward Lloyd bought it in 1877, and, dropping the sub-title of the Clerkenwell News, launched boldly into the ever-swelling tide of London daily journalism. Mr. Lloyd died a year or so ago, the possessor of a great fortune, and of a reputation as one of the shrewdest and most long-headed organisers of modern industry. In the course of a long life he had built up from the smallest possible beginnings two great newspapers, and what is to-day the largest paper- making establishment in England, and possibly in the world. The great firm of Lloyd’s, with headquarters at the fine new mills at Sittingbourne, turning out a maximum of three hundred tons of paper a week, makes not only for the Chronicle and for newspapers all over England, but for the greater portion of the Australian press. Considering that the circulation of Lloyd’s has reached the enormous figure of three-quarters of a million a week, it can be imagined what this vast output means. Mr. Lloyd had many remarkable qualities, chief among which was his excellent judgment and unfailing capacity for looking ahead. A quiet, silent, and much observing man, he was responsible for the introduction in any large quantities of the material known as esparto grass, which is still used in the manufacture of all kinds of paper. The actual discovery was made, I believe, by a Mr. Routledge, a paper-maker in the north of England, but to Mr. Lloyd was due its wide use in this country. To-day the proportion of esparto grass to other materials has diminished for all but fine writing papers, and it is largely replaced by wood and other substances. It is from the forests of Norway and Sweden that the British public is largely fed with its news-sheets. The Messrs. Lloyd have therefore abandoned the direct culture of the tough and wiry grass grown on vast farms in Algeria, one of the largest of which was bought and worked by the late Mr. Lloyd.

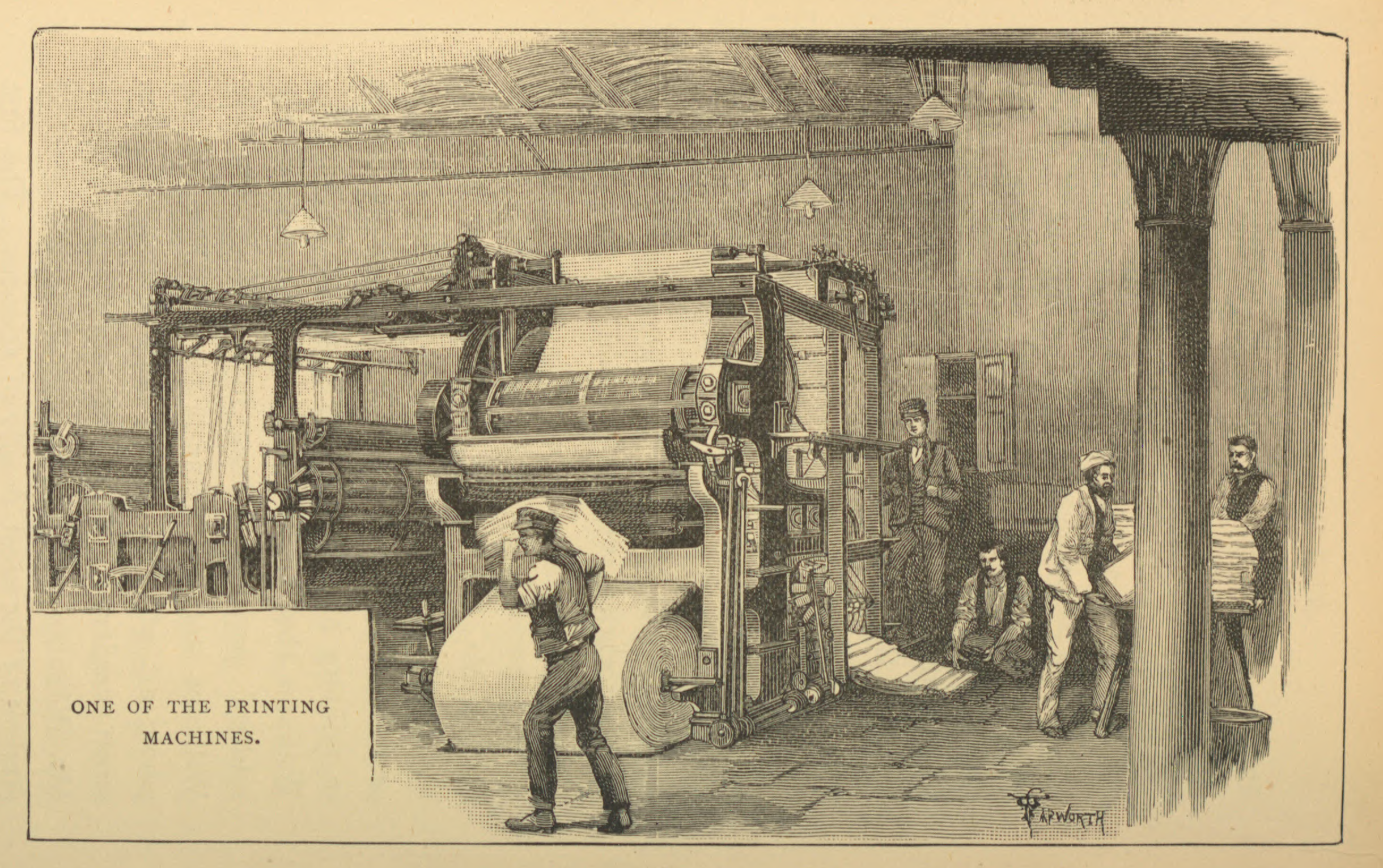

Since Mr. Lloyd’s death, the direction of the Sittingbourne Mills and of the two newspaper properties which depend upon them has passed into the hands of his son, Mr. Frank Lloyd, a man who combines his father’s organising genius with wide social sympathies, and with a real share in the intellectual interests of the age. The employees at the Sittingbourne Mills have a band, a cricket club, and other institutions which Mr. Lloyd is careful to foster. He possesses, too, something of the born journalist’s zest for affairs, the quality which has so much to do with the wise direction of newspapers. Mr. Frank Lloyd is assisted in the directorate by his three brothers, Messrs. Arthur, Herbert, and Harry Lloyd. Under his regime the mechanical production of the paper has been enormously improved, and the Daily Chronicle, the latest comer in London journalism, has been the first to employ, on a large scale, the fastest, surest, and deftest machine known to the printing world. To-day the Chronicle would be able, on pressure, to produce in a single night from its eight new double Hoe machines as many twelve-page papers, consisting of nine columns to the page, as the London and provincial market could possibly demand of it. Each paper, moreover, would be gummed and folded ready for the agents’ hands, and would be produced with perfect neatness and evenness of imprint.

Editorial staff and correspondents

The editor of the Chronicle is Mr. Alfred Ewen Fletcher, a Lincolnshire man, educated at Edinburgh University, who, apart from his long connection with the Chronicle, made his chief mark as editor of the Cyclopedia of Education. He was assistant-editor of the paper in the days when the late Mr. Whelan Boyle was in the chair. It cannot be said, however, that Mr. Boyle, a careful and pains-taking editor of the old school, left any decisive mark on the Chronicle; its history as an organ of opinion dates mainly from Mr. Fletcher's appointment. The London press is served by editors of varying types, but nearly all of them, I think, are deficient in the quality which has helped so largely to give the Chronicle its vogue and name. A wise, careful, experienced, and perspicuous journalist, Mr. Fletcher joins to these gifts a real love of literature, a special knowledge of educational questions, and a sympathetic temper, which readily grasped the significance of the labour movement which began with the Dock Strike of 1889. A year or so ago the Star represented the most complete embodiment of the London democracy, but to-day its place has been taken by an organ which, curiously enough, does not stand in complete accord with the main body of the Liberal party. Simultaneously with this change, the Chronicle has, under Mr. Fletcher’s guidance, touched a new, and in some respects unapproached, standard of literary excellence, largely due to the fact that its writers specialise their subjects much more thoroughly than on any other London paper, save the Times. The day of the all-round journalist who knew a little of everything, and nothing thoroughly, is pretty well over, and to him has succeeded a class of men with a more thorough intellectual equipment and more strenuously pursued ideals. On the Daily Chronicle social, religious, labour, colonial, and military questions are all deputed to men who may fairly claim the character of experts. Conspicuous among them are Mr. James Milne, Mr. Naylor, and Mr. Morrison, who watch labour and religious subjects. On the other hand, no paper presents a wider or more carefully selected variety of news, with the result that it is to-day by far the most fruitful of the many hunting-grounds of the sub-editor of the evening newspaper. The sub-editorial department is in the hands of Mr.Charles Sharp, a careful and experienced journalist, who has served on the paper since its origin. Mr. Sharp has eight assistants. This is a sufficient testimony to the importance the Chronicle attaches to the collation of its news. No department, however, of the staff has been better organised than its foreign and colonial intelligence, in which it is admirably represented abroad by men like Mr. Millage, its Paris Correspondent, and Dr. Horowitz, its representative in Vienna, while the whole is arranged by Mr. W. J. Fisher and Mr. Heron, journalists of great knowledge and experience, as well as excellent judgment. The Parliamentary staff is under the direction of Mr. S. J. Fisher, an old ’galley’ hand; and the dramatic and musical news and criticism are contributed by Mr. John Northcote and Mr. Townley ’Jeffrey Thorn’. Mr. A. H. Hance is the shrewd and capable business manager.

The Chronicle is served on its leader-writing staff by a man of singular ability and wide and really brilliant attainments in the person of Mr. Robert Wilson, who has in his time been assistant-editor of the Standard and a leader-writer on the Telegraph. Mr. Wilson is a Scotchman, and if he has something of the perfervidum ingeninm of his race, he possesses also a power and critical grasp that are all his own. No London journalist excels, or probably equals, him in knowledge of Victorian history, and his singularly pointed pen often recalls the work of Abraham Hayward, to which for wide and curious culture, for wealth of illustration, and for mordant power his best writing offers some resemblance. Mr. Wilson’s memory is a storehouse of facts, and he touches no subject without enriching it with a vein of suggestion. Mr. O'Connor Power, one of the most polished orators that the House of Commons has ever known, has also a large and useful share in the formation of Chronicle opinion; and yet a third leader-writer is Mr. William Clarke, an economist, an historical student, an expert in American literature, and a man of vigorous character, of real insight, and of sound critical judgment. Mr. Francis Storr, the able editor of The Journal of Education, is a frequent contributor of articles and notes on educational subjects. The daily literary supplement is sustained by writers of the type of Dr. Jessopp, Mr. A. B. Walkley, Mr. Bernard Shaw, Mr. Morrison Davidson, Mr. Le Gallienne, Mr. John Rae, Mr. Balsillie (who writes on theological and metaphysical subjects), and Professor Murison, as well as by the regular members of the staff. The experiment of a serial story, which was associated with the days when the Chronicle projected a weekly instead of a daily literary supplement, has been suspended, subject, I should say, to a possible revival.

An especially valued member of the Chronicle staff is Mr. Charles Williams, who acts for it in the double capacity of a war-correspondent whose services are permanently retained and an expert in military affairs. It is very largely due to Mr. Williams that the Chronicle is par excellence the soldiers' paper. Among living journalists Mr. Williams stands supreme in his knowledge of the whole art of war. A bronzed veteran who has smelt powder in almost every quarter of the world, Mr. Williams is a close, enthusiastic, and learned student of the most deadly of sciences. The first editor of the Evening Standard, and an old friend and colleague of Mr. Mudford, Mr. Williams is a Tory on Imperial lines, with a certain dash of democratic feeling which made him and Mr. John Burns excellent friends during the Dock Strike. In military matters Mr. Williams is a bit of a Wolseleyite, and on this question and on others he now and then finds himself in opposite camps to his good friend Mr. Archibald Forbes. An all-round journalist of wide experience, large descriptive powers, and a most fertile pen, Mr. Williams serves his paper with equal diligence and ability.

Hoe printing presses

The Daily Chronicle is housed in a rather shapeless group of buildings, which straggles round the corner of Fleet Street and winds into Salisbury Court, where it joins on with the business offices of the firm of Lloyds. In order to minimise the risk of fire, the rooms were almost entirely built of iron and concrete, the doors of the older portion of the building being all of iron. The composing room is a cool airy structure, lighted throughout by electricity, where one hundred men, including some of the fastest compositors in London, are at work. The mechanical interests of the Chronicle, however, are centred largely in the machine-room with its eight double Hoes, which could at a pinch produce a daily paper at the rate of 200,000 copies an hour. The new Hoes are provided with the simple and ingenious arrangement known as a ‘gummer.’ The gummer, or rather gummers, for there are two of them, one for the literary supplement and one for the rest of the sheets, are metal discs revolving in paste-pots, which lightly attach the pages as the sheet whirls past them.

` |

| Hoe web printing press at the Daily Chronicle. |

The invention has long been in use in America, and it is a testimony to the inveterate conservatism of the English press that its introduction here has been so long delayed. The Chronicle, Standard, and Telegraph, however, all employ it, leaving the Times and the Daily News content with the older arrangement. In the stereotyping department the Chronicle, like the Telegraph, employs the ‘cold’ in addition to the ‘hot’ process, and it aims specially at leisurely and competent production. Curiously enough. Mr. John Burns, working as an engineer, helped to build one of the Hoe machines in use during the Dock Strike.

Sittingbourne Paper Mills

It seems natural to associate the Chronicle with the huge paper mills from which it and its companion paper grew. Mr. Edward Lloyd’s old mill was fixed at Bow, and remained there until the befouling of the Lea forced its owner to go further afield for pure water. He found this at Sittingbourne, where his present factory is established, and where are stacked the huge stores of wood, already partially reduced to pulp, esparto grass, and all the other materials which the modern papermaker is able to work into his fabrics. The mountainous piles, however, only represent a few weeks’ stock, soon to be boiled, bleached, beaten, and shaken into the huge wound reel from which the modern printing press is fed. The processes are various enough. First the esparto, which is used to the extent of twenty per cent, for the ordinary news-sheet, and the straw are boiled in monstrous vats, while the wood goes straight to the bleaching and washing machines, where the impurities disappear and the whole fibrous mass is made fit for the second process of beating or grinding between revolving knives, which reduce it to a finer and softer consistency. At a further stage it is dexterously relieved of the knots and unbeaten morsels that still encumber it, until it pours, a milky mass, on to a bed of very fine wire with a tremulous lateral movement which shakes the loose fibres together. The water is then sucked off in vacuum boxes underneath the bed, and in a second, as it were, you can see the little milk-white river harden into the roll of virgin paper. This, when it has been squeezed between one set of cylinders and dried between another, appears in the shape in which, save for a final damping process, it is ready for the press. Finally, the reels are hoisted into a small fleet of barges, and are carried up the wide reaches of the Medway and Thames to their goal in London, or Sydney, or Melbourne.

The Daily Chronicle has perhaps a more interesting, and at the same time a more indeterminate, future than that of any other English paper. It has practically ceased to represent any militant form of Unionism, and its free and intelligent expression of the later movements of advanced social opinion will probably bring it more or less in touch with the New Radical party. Or it may possibly resist the inevitable attraction which a political organisation possesses for a daily journal an attraction, however, which its rival, the Telegraph manages more or less to ward off and remain a paper with a message and a mission, but without a client. Its hold on London is unquestioned. It is the only paper which shares with the Telegraph the character of an informal labour bureau, where the great want of the modern world the want of work and of workers is daily supplied in sheet after sheet of closely-printed advertisements. Meanwhile, the tendency to which I have already referred, that of appropriating subjects especially notable in its labour and its religious news, and its reports of the doings of the London County Council while it keeps the Chronicle in touch with some main pulsations of modern English life, contrasts rather piquantly with its shyness on the Irish question. The paper which interprets so many new demands, the zeal for culture, for social, religious, and temperance reforms, for municipal extension, is likely to aspire to have a decisive word in the political controversy of the hour. It is not surprising, therefore, that no inquiry is more frequently on the lips of the average party man than ‘How is the Chronicle going on Home Rule?’ For the present, however, it is enough to say that, while it influences all parties, it definitely espouses the cause of none, and remains in the powerful position of a critic at large. Withal its circulation increases daily. Its liveliness, variety, serious tone, and intellectual thoroughness afford a welcome relief to the slovenly and unthinking opportunism which is the curse of the modern newspaper. In a word, it has gone far, and it ought to go farther.

Footnotes

- 1 Massingham, H.W., The London Daily Press (New York: Revell, 1892), 121–144.