Romances and Penny Serials

Lloyd started publishing stories in parts in 1835 with series featuring well-known pirates and highwaymen. These were followed in 1836 by the Penny Pickwick, other Dickens’ parodies and soon after by serialisations of original material. He called them romances, but the early focus on bloodthirsty goings-on stuck and they came to be known as ‘penny bloods’. Lloyd became the undisputed market leader. His romances were so prolific and successful that the new genre was known as the ‘Salisbury Square School of Fiction’, named after the address south of Fleet Street to which he moved in 1843.

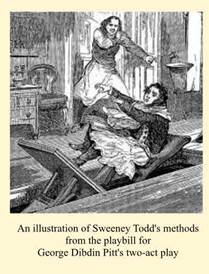

The length of stories depended on their success week by week, ranging from 6 to 206

instalments. The best remembered is The String of Pearls i.e. (Sweeney Todd, 1846-47).

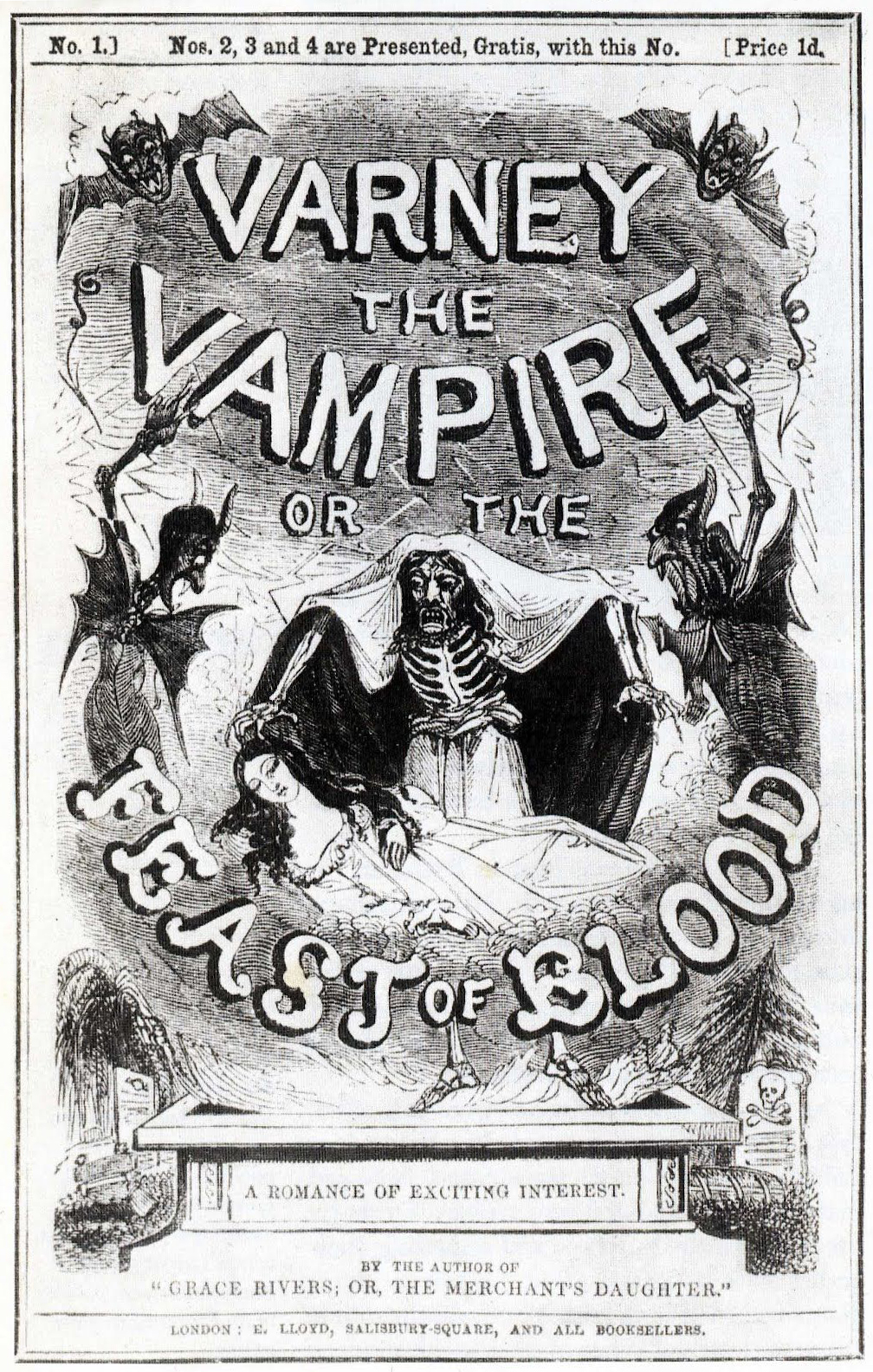

He also brought vampires, already popular among the literati, to a mass market

readership (Varney the Vampire, 1845-47). These two and several others were re-issued later.

Weekly numbers were also made available as a compendium at a higher price and some

were made into bound volumes.

He kept what was published under tight control. A letter to the New York Times

described his work methods: “He would interrupt the chat to speak through tubes

to author, printer, and publishing office from his chair, as 'How is Paul and the

Pressgang going?' and communicate the instructions from the reply: 'Tell Mr. Scribe

to keep Paul Pressgang four numbers ahead' or 'Scribe, just wind up Pressgang in

two issues and get on with The Dumb Boy of Manchester — the play is a hit at the

Adelphi'.” Admittedly, the letter was written in 1904 but it must have drawn on

a contemporaneous memory.

The length of stories depended on their success week by week, ranging from 6 to 206

instalments. The best remembered is The String of Pearls i.e. (Sweeney Todd, 1846-47).

He also brought vampires, already popular among the literati, to a mass market

readership (Varney the Vampire, 1845-47). These two and several others were re-issued later.

Weekly numbers were also made available as a compendium at a higher price and some

were made into bound volumes.

He kept what was published under tight control. A letter to the New York Times

described his work methods: “He would interrupt the chat to speak through tubes

to author, printer, and publishing office from his chair, as 'How is Paul and the

Pressgang going?' and communicate the instructions from the reply: 'Tell Mr. Scribe

to keep Paul Pressgang four numbers ahead' or 'Scribe, just wind up Pressgang in

two issues and get on with The Dumb Boy of Manchester — the play is a hit at the

Adelphi'.” Admittedly, the letter was written in 1904 but it must have drawn on

a contemporaneous memory.

According to Price One Penny (POP), his serialisations became systematic in 1838,

reached a high point in 1847, tailed off after 1852 and stopped altogether in

1854 (this may not be entirely accurate as not all the romances listed are dated).

Helen Smith notes a remainders sale in 1861.

According to Price One Penny (POP), his serialisations became systematic in 1838,

reached a high point in 1847, tailed off after 1852 and stopped altogether in

1854 (this may not be entirely accurate as not all the romances listed are dated).

Helen Smith notes a remainders sale in 1861.

POP lists 201 romances, outnumbering his closest competitors nearly five times over (his nearest rival, George Pierce, published 44, with George Purkess and Henry Lea runners up with 42). However, this may be an under-estimate. Sarah Lill believes that Lloyd may have published up to 230.

Helen Smith reproduces an 1846 “List of Cheap Publications Now Publishing” (p.15). Updated every six months, it indicated the scale of Lloyd’s output — 27 current romances in penny numbers or bundles, one magazine, one song-book, 28 full-length compendiums and 18 cloth-bound books.

Descriptions were euphoric: engravings were never less than “superior” or "first-rate", illustrations “superb” or “beautiful", and Lloyd’s Penny Sunday Times was “this Cheap Colossus of the Press”. It claimed that Gallant Tom, "the Most Popular Nautical Romance Ever Published", had sold “upwards of” 100,000, been copied in America and “speedily went through 22 editions”. Sales of the Penny Sunday Times were said to be 60,000.

One cannot know whether these numbers were accurate, euphoric or a rounded-up estimate. Lloyd would have kept exact records himself but there was no common system of recording circulation until the ABC was introduced in 1931 for the purpose of pricing advertising.

Lloyd’s Penny Weekly Miscellany of Romance and General Interest was a magazine that contained the instalments of several stories running concurrently. The first compilation volume, published in 1843, has been digitised. It runs to 862 pages.

Lloyd issued one deliberately up-market publication — Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (1847, in 39 parts). It was lavishly illustrated and printed on fine paper but still sold for 1d. It may be no coincidence that this venture preceded his insolvency in 1848, adding to the losses on Lloyd’s Weekly.

Mainstream fictional serialisations, such as those by Charles Dickens, typically

cost 6-12 times as much as the penny that Lloyd charged. Because of this and a

smattering of gruesome plots throughout this period, Lloyd is treated as having

created the “penny blood” phenomenon. (The term “penny dreadful” was coined later

in the century, long after Lloyd had abandoned them.)

Mainstream fictional serialisations, such as those by Charles Dickens, typically

cost 6-12 times as much as the penny that Lloyd charged. Because of this and a

smattering of gruesome plots throughout this period, Lloyd is treated as having

created the “penny blood” phenomenon. (The term “penny dreadful” was coined later

in the century, long after Lloyd had abandoned them.)

In fact, the bulk of his output in the 1840s matched his own description, “romances", more closely. The term was broader than it is now — sensational tales of love and adventure, extravagantly portrayed and often spiced with the supernatural.

George Purkess (1802-62) was an occasional associate. They co-published seven romances in the 1840s, two with William Strange, a pioneer of the penny press.