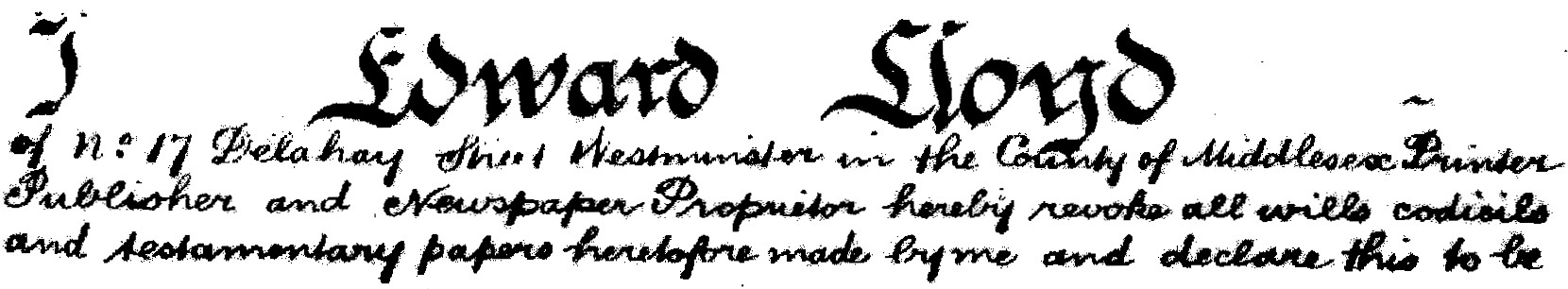

Edward Lloyd’s will

The will is difficult document to read. It is written over seven pages in copperplate with no punctuation, sentences or paragraphs. Moreover, it is so ambiguous in parts that his heirs had to get legal advice after Lloyd’s death, then again after Maria’s death, and again when the trust was wound up in 1911.

Before he died, Lloyd set up a Trust independent of his will. Slightly more than half the shares in Edward Lloyd Ltd were held by four of his sons in trust for the grandchildren, with the children entitled only to a life interest. The will provided generously for Maria, giving her all personal and household effects and the right to live in or receive the rent from three of Edward’s properties. In addition to receiving an income equal to the sons’ shares, she received an annuity of £1,000.

Lloyd was anxious to protect his daughters from fortune hunters, reserving the benefits “given to females … for their sole and separate use independently of their husbands and without power of anticipation”. As this clearly refers to the daughters while alive, the Rev Coggin, whose wife died in 1905 after bearing four children, was entitled to succeed, although the clause about surviving spouses is poorly drafted.

While Maria lived, Edward ordained a curiously sexist disposition. Sons received 10% of the income from the estate while daughters received only 2.5%, although the four unmarried daughters could ask their mother to let them live with her.

|

| Maria and some of the children in the 1890s |

In the event, this discriminatory regime only lasted for three years. After Maria's death, the four sons who had helped their father build up the business received large shares (18% to Frank, 12% to Frederick and 10% each to Herbert and Arthur). Harry, who was also active in the business, was not so singled out. Most of the other sons and all the daughters received 5% each (about £28,000).

Lloyd's sons by Isabella, Edward and Charles, were not included in the residual estate. Instead, they each received fixed gifts of £6,000 and an annuity of £400. Both had married late in life and were childless, and although they had started out working for their father, they persued their own careers separate from the business.

Of Maria's children, annuities were to be paid to Ernest, a proven profligate, and Thomas, who suffered from a disability of some sort. Annuities were paid to Maria's sister and Edward's nephew Charles, who was an executor, and smaller gifts were made to another nephew, two named employees and all staff of more than 20 years’ standing. Sadly, this last group didn't include another his great-nephew Edward—son of Evan through his middle brother William as he had only at the Sittingbourne mill from 1871.

None of the heirs were to receive their share of the estate's capital for 21 years, i.e. 1911. After that, the trust had to continue for the payment of various annuities, but the bulk of the capital could be distributed.

Release was delayed, however, and a letter dated 16 June 1913 from the will trust's solicitors to Rosalie McRae urged her to sign the deed of release from the trust, noting that “each of the beneficiaries has received his or her full share of the estate exclusive of the securities and balance of cash retained by the executors to meet the annuities.” Percy had commissioned an audit of the trust accounts. This having been achieved, Rosalie was still reluctant to sign the deed.

The will trust was finally wound up in 1926 following the death of all the annuitants.

It is as well that Edward survived his illness in 1889, had he died intestate, his whole estate would have gone only to his legitimate heirs, Edward, Charles, Florence, Percy, Rosalie and Laura.