The Daily Chronicle

The Daily Chronicle established Edward Lloyd as a leading presence in Fleet Street. His talents created a newspaper that the public enjoyed reading and one that was delivered with all the efficiency that modern technology could muster.

After Lloyd‘s death, the paper grew in controversy and political influence under editors who were among the leading journalists of the time, such as Henry Massingham and Robert Donald. Its popularity arose from its extensive reporting of the news, however, and that did not change.

Despite claiming to be a Liberal paper, its political position was often to the left even of the “independent” arm of the Liberal Party. Its own independence proved to be its downfall in 1918 when, after defying Lloyd George, it was bought out by the Prime Minister‘s political friends.

The new paper was built on the foundations of the London Daily Chronicle and Clerkenwell News. This had been set up as a modest 4-page weekly in 1855 called the Clerkenwell News and Daily Intelligencer. By 1876, when Lloyd bought it, it was a successful local daily serving the poor neighbourhood to the west of the City where watch-making was the leading trade. About half was taken up by small ads.

Lloyd paid £30,000 for it. The owner was pleased with this price1, although it was hardly generous if Catling was correct in putting the profits at £5,000 a year2 (this sum may have been exaggerated—it was disclosed in a battle with the Revenue). Lloyd spent a further £150,000 on transforming it. The total would have been nearly £19m in today‘s money.

Its name was changed to Daily Chronicle on 25 November 1872 but it was still essentially a local London paper. Lloyd launched it as a national daily on 28 May 1877. In an unusual show of modesty, there was no great fanfare in Lloyd‘s Weekly. A column of small ads in the 27 May 1877 edition claimed the Chronicle’s many virtues, including “Latest News From All Parts of England”.

The development plan was kept secret from the outside world.3And the surprise proved its worth by generating intense public interest. The public liked what they read. The circulation rose from 40,000 to 200,000 the following year.

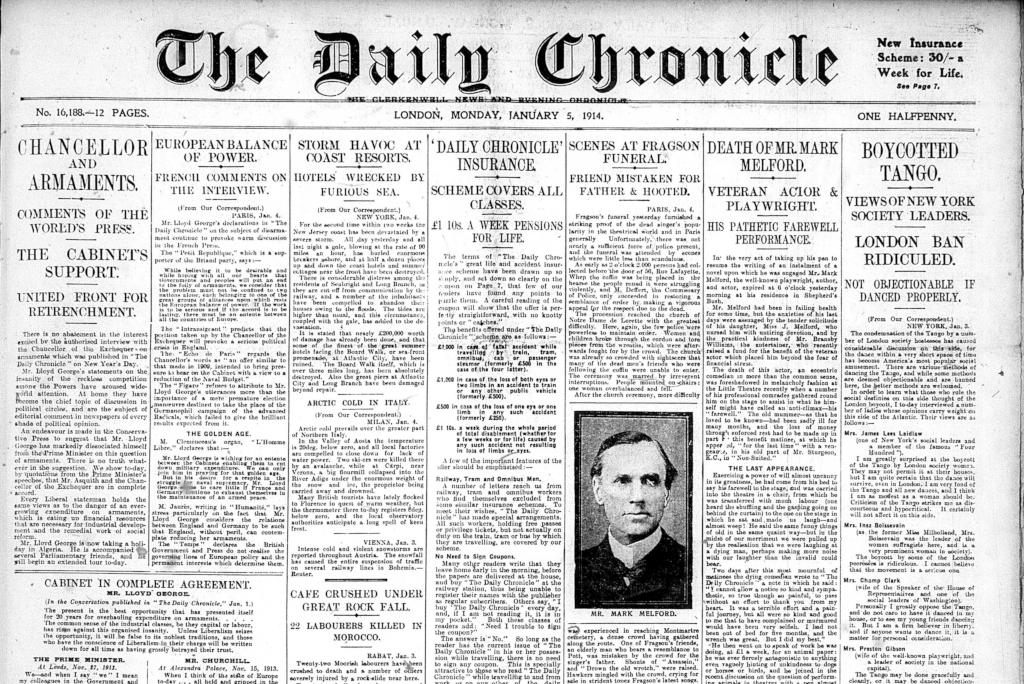

Alan Lee in The Origins of the Popular Press in England4 reports sales of 400,000 in 1914, doubling within a year. The editor claimed that it was outselling four major dailies and an evening paper put together. After its sale, circulation is believed to have grown to 1,400,000 in the late 1920s before disastrously falling off in 1929-30.

|

| Chancellor and Armaments in The Daily Chronicle 5 Jan 1914 |

Success

Lloyd applied his formula for a popular newspaper—broad news coverage, variety of content (with close attention to books and the theatre), plain-spoken leaders and good general readability.

The paper was especially valued for its news reporting. In 1896, a short-lived journal called Book Bits wrote: “Its strength seems to lie outside politics, for it is read, not for what it says about Liberal or Conservative, nor for the sensationalism which is the mainstay of some other papers, but chiefly for its accurate representation of what is going on around us.” In the late 1880s, the paper had introduced colonial news under the title “Greater Britain Day by Day”.

Henry Massingham, who joined the paper in 1891, noticed that many of those who wrote for the paper were specialists in their field—social, religious, labour, colonial, military, arts, whatever. The Chronicle achieved this “much more thoroughly than any other London paper”.5

Notable scoops included the suicide pact between Crown Prince Rudolf and his mistress at Mayerling in 1889, and a pivotal rebellion in the Balkan Wars of the 1880s. It repeatedly broke news of travels and triumphs by explorers and mountaineers—a particularly popular line.

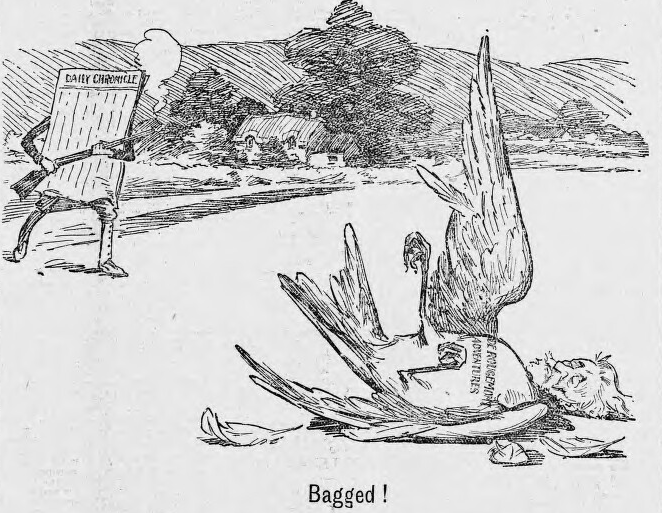

In 1898, helped by a lively corresondence column, it unmasked the “De Rougemont” hoax travelogue: Henri Louis Becke (later Grin) described the absurdly improbable adventures of a fake explorer. He later toured South Africa as a music hall turn called “the greatest liar on earth”. The bird shot by the Chronicle in the cartoon is called “The Rougemont Adventurer” (Chronicle, 15 October 1898).

|

| Bagged! a cartoon in the Evening Express, 1898 |

Despite their differences of political outlook, the Chronicle competed with the Telegraph for the middle market—a section of the reading public described by Massingham condescendingly as “the clerk, the shopkeeper and the great mass of villadom” (suburbia). Both titles recognised that most people were interested in news beyond the narrow political scene in London that dominated the quality papers. Another arena for rivalry was recruitment advertising.

Editors

The Chronicle was too large an operation for Lloyd to wield as powerful a controlling hand as he could over Lloyd‘s Weekly. Although he was attentive to all its concerns, the editor was a true editor, not just a leader writer.

Affectionate portraits of Fletcher and Massingham at work, particularly their enthusiasm for reviewing books, were written by James Milne in 1931.6 The Chronicle was supposed to be at “the other end of the book-buying classes” but why should books not be brought within the knowledge of the man in the street? Essays written for the Chronicle in 1900, collected in The Mind of the Century, are evidence that it was not afraid to include serious-minded material.7

Massingham strongly believed in diplomacy rather than war and did not hesitate to make the point on several occasions. For example, a boundary dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana in 1895 became an incident when the US insisted on arbitration—a position that Massingham advocated. Eventually the UK agreed to it and was rewarded by getting 90% of what it wanted.

When news of the Armenian massacre broke in 1895, he pressed Gladstone into expressing dismay. Nothing further followed, however, leaving a sore that still festers.

The Chronicle used the services of the renowned war reporter, Henry Nevinson, to write about the Greek-Turkish War in 1897, the Boer War of 1899-1902 and the St Petersburg riots in 1905.

Massingham had to resign in 1899 after his outspoken opposition to the Boer War caused circulation to fall off. Jingoism played its part, but the many readers with sons, brothers, husbands or friends fighting for Empire in South Africa did not appreciate the idea that their sacrifice was worthless. This, rather than political allegiance or enthusiasm, was a reason for the tendency of even the radical press to support the war after 1914.

William James English Fisher was appointed editor in 1899. He had been foreign editor from 1883 until 1894 when he became assistant editor. He stood for Parliament unsuccessfully as the Liberal candidate for Canterbury in 1905 and 1910. Little is recorded about him.

Robert Donald was appointed in 1904. He was editor of both the Chronicle and Lloyd‘s Weekly until 1918 and a director of United Newspapers, the company set up by the Lloyd family to manage Edward Lloyd‘s publishing empire. He had a diversified career, joining the Chronicle in 1895 as news editor, but leaving in 1899 to promote a hotel group—useful business experience no doubt, but an eccentric move for a journalist at that time.

Throughout the war, the Chronicle did not hesitate to criticise Lloyd George‘s policies when it considered that he was taking a wrong direction. The Prime Minister nevertheless found the Chronicle to be fairer and friendlier overall than other papers, apart from the Tory titles.

Donald was willing to follow the government‘s view when he believed that it served the public interest. He was appointed “director of propaganda in neutral countries” in the Ministry of Information in February 1918—a wartime arrangement that he had advised the government to set up. He was the only active journalist involved, the others being two proprietors, John Buchan and a politician.

The Chronicle was supportive of the armed forces and, when they were in conflict with government, it tended to side with the generals. By 1918, Lloyd George was seriously at odds with Sir William Robertson, the Chief of Staff, whom he believed to have been orchestrating a hostile press campaign.

Donald was dogged in doing what he thought was right. A friendly relationship with the Prime Minister and a government role did not make him Lloyd George‘s lapdog.

Lloyd George‘s misjudgment of Donald‘s character in 1918 closes the book on the involvement of Edward Lloyd and his family in newspapers.

Lloyd George’s coup

On 9 April 1918, Lloyd George told the House of Commons that the British army had not been weakened numerically before the German onslaught in March 1918. Sir Frederick Maurice, the Director of Military Operations responsible for compiling the statistics, knew that this was not true. He wrote to the Chief of Staff but received no reply.

After much thought, he decided that the right thing to do was to expose the deception. On 7 May, he sent a letter disclosing the true figures to all the major papers. On 9 May, Maurice was forced to resign, so losing the opportunity for a judicial process in which he could have defended himself. The Chronicle reported the Commons debate that followed dispassionately, but Robert Donald did something far more inflammatory—he offered Maurice the job of military correspondent a few days later. Maurice accepted and proceeded not only to enhance the Chronicle‘s pro-generals coverage, but also to hit back at the Prime Minister.

Lloyd George vowed revenge and persuaded a group of friends, led by Sir Henry Dalziel, already a newspaper proprietor, to buy the Chronicle and give him editorial control. It is almost certain that some of the necessary capital was raised by selling peerages. On 5 October 1918, the new regime took over at 6 p.m. Donald and Maurice resigned.

Donald had been taken by surprise. The first he heard of the sale was on 3 October. Incredulous, he only discovered the truth when he spoke to Frank Lloyd on 4 October. That he was kept in ignorance does not speak well of Frank‘s loyalty to an exemplary and long-serving editor who had done nothing but good for the standing and profitability of the Chronicle. Donald was also a director of United Newspapers alongside Frank.

Frank may have had to agree to keeping the negotiations confidential. That he extracted the huge sum of £1.6m from the manipulative Lloyd George is undoubtedly satisfying, but what was probably his main motive—the further enrichment of the Lloyd family—is less so. A more worthy motive for keeping Donald in the dark would have been to stop Donald behaving in an unpredictable and possibly extreme fashion to the detriment of Frank‘s bargaining power.

This extraordinary story of political interference with the press is well known but it still has the power to shock. It did not happen entirely out of the blue, however. Lloyd George had already made a botched attempt to expropriate the Chronicle. Early in 1917, he had amassed offers worth £650,000. Frank Lloyd named his price as £900,000. This effort ground to a halt on discovery that Lord Beaverbrook was behind the move. He not only owned the Express, a competitor, but he was a Tory.

The Chronicle‘s independence was viewed as second to none by New Zealand Truth in October 1918: the best sources of news about the war and the Russian Revolution had been the Chronicle, Daily News and Manchester Guardian. The Chronicle was “not so radical and so much inclined towards the speedy making of peace” as the Daily News. It was “now a more important paper than ever it was”.8

The story of this earlier attempt to silence the Chronicle was told by by J.M. McEwen in 1982 and of the eventual sale, he wrote:

A fine paper lost its independence and the press as a whole was the loser; a first-class editor was destroyed; an aggressive young “press lord” who held ministerial office was deprived of his quarry; and a famous prime minister ventured into unknown territory to spend heavily from a treasury that was not quite his own.9

Coda

In 1927, the two Lloyd newspapers fell into the hands of regular investors when Lloyd George sold his interest and United Newspapers was listed as a public company. The Chronicle‘s remaining years are interesting but have no relevance to the Lloyd story.

Lloyd George‘s was the only name on the sale document, and the price paid was £2.9m (nearly £163m now). Those who had bought the paper for him in 1918 had already sold their shares to him, presumably at its earlier value, but the fate of the Liberal Party‘s share of the profit, estimated at £1m, created some controversy.

His prowess at financial manipulation did not end with making a supranormal profit. He also retained control of the paper‘s editorial policy without bearing any risk from its liabilities. The sale agreement contained a clause pledging the paper to follow “Progressive Liberal” policies, eschewing both reactionary and communist-leaning doctrines. Should it fail to do so, Lloyd George had a right of pre-emption for ten years after the sale.

In fact, his political control of editorial policy, though watchful, had been “remote, invisible and little-comprehended to those who handled the copy” according to Guy Schofield in The Men that Carry the News (Cranford Press, 1974).

If, as some reports say, the agreement also guaranteed shareholders a 10% dividend—a wholly unrealistic return on capital in the volatile newspaper business—ruin was on its way regardless of the impending financial crisis. The owners in the years 1927-30 had little or no experience of running a newspaper.

In 1930, the Chronicle was insolvent. Schofield wrote that its debts were already overwhelming, every day was adding to the losses and it was losing readers. At the end of May, rumours began to circulate in Fleet Street and the City.

Before they could be verified, merger with the Daily News was announced on 1 June, taking the world by surprise. “To journalists it was a heartbreaking decision,” Schofield wrote. The merger was in fact a takeover. The Chronicle bore the lion‘s share of the redundancies. Its Leeds operation, started in 1925, simply closed down with the loss of all jobs.

United continued as equal owner until 1936 when Daily News Ltd became the sole shareholder. The purchase price—a valuation of the copyright in the paper—was about £1m (£63m now). That cleared United‘s debts.

In 1958, after at least two decades of prosperity, the News Chronicle and its companion, the Star, were again in financial trouble. In an echo of earlier times, the Chronicle lost readers by opposing the government‘s policy in the 1956 Suez crisis. It failed to recover.

To avert further losses, the Cadbury interests decided to kill the papers. Their choice of executioner was odd—Associated Newspapers, owner of the Daily Mail. It may be that theirs was the only deal on offer, of course.

Associated paid £2m (£41.7m now) for an option to buy the premises, plant and goodwill. No offer to continue publishing the paper was on the table. After giving it two years to boost sales, Associated took up the option in August 1960.

The last vestige of Lloyd‘s newspaper empire thus succumbed to summary execution by the Daily Mail. An account appears in Murder will out (Spectator, 21 October 1960, p.3), but it has to be conceded that Associated was not quite the villain that it appears to be at first sight.

A sad but telling episode that followed deserves a mention. The board of Daily News Ltd decided to devote the £2m paid by Associated to compensating the staff. Part of this was a voluntary gesture by the board, not required by law. The High Court, in Parke v Daily News [1962] Ch 927, ruled that the interests of the shareholders prevailed over a gratuitous donation to ex-employees. The board had no power to be generous with the shareholders‘ money.

Footnotes

- 1 Catling, p126

- 2 Catling, p142

- 3 Catling, p126

- 4 Lee, Alan J., The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855-1914 (London, 1976), 162-67.

- 5 Massingham, Henry, The London Daily Press (New York: Revell, 1892).

- 6 Milne, James, A Window in Fleet Street (London: John Murray, 1931), p287.

- 7 The Mind of the Century (London: Fisher Unwin, 1900).

- 8 British Newspaper Combines, and the People, New Zealand Truth (19 Oct 1918), 1.

- 9 McEwen, J.M. ‘Lloyd George‘s Acquisition of the DailyChronicle in 1918’, Journal of British Studies, Vol 2, No 1, Autumn 1982, pp.127–143.